Fighting on the Frontlines: Judges join the fight against opioids

With the opioid crisis creeping its way into courtrooms, judges are joining the fight against the epidemic. ABC 57 traveled from Michiana to Indianapolis to find out how judicial leaders are tackling the problem.

“It’s powerful. You know, you know it’s wrong, and you know what you need to do, but it’s hard. It takes over your mind,” said Sherry Eskridge, a recovering addict who lives in Starke County.

27-year-old Eskridge has been battling her heroin addiction for nearly ten years, but just this year, she got arrested for the first time for Possession of Heroin.

She now joins the 24,000 incarcerated people in Indiana, which amounts to more than 50%, who are struggling with substance abuse as of September 2017, according to Indiana University School of Public Health and the Department of Corrections.

“I mean there’s almost not a day that a drug case doesn’t come before us,” said Indiana Chief Justice Loretta Rush.

That’s why Chief Justice Rush is joining at least seven other state chief justices in a new national task force to re-evaluate their rulings on opioid cases.

“They asked me to be chair, and frankly how do you not? This is one of the biggest things, biggest crisis that has affected our branch of government on top of the public health. I mean we’re losing so many people right now to this crisis,” said Chief Justice Rush.

Some of those people are Sherry’s friends and family.

“It’s a hard thing to get away from. It’s something that grips onto you and doesn’t want to let go,” said Sherry.

To figure out how to get heroin to loosen its grip on the courts, Chief Justice Rush said they traveled the state and spoke with the hundreds of trial court judges across the counties.

She said the theme that kept coming up time and time again is that trial courts are being overwhelmed with substance abuse cases.

Starke County Circuit Court Judge Kim Hall has been working in the judicial system, prosecuting and presiding for over 30 years.

“People who I started with prosecuting, they were 25, and now they’re in the their 50s, and they’re still here in our jail…so we can’t continue doing what we’ve been doing and expect results to be any different," said Judge Hall.

In fact, he says three out of every four cases that come through his courtroom are drug-related.

10 years ago, it was one in three.

“So what we have going on is the legal system analyzing their legal rights and spending a lot of resources in that field when really they’re using every day,” said Judge Kim Hall.

“I didn’t stay clean the whole time I was on pre-trial home detention,” said Eskridge.

“Unfortunately often, they’ll get another charge in 30 days or 90 days, because they feel I can use until my case is over,” said Starke County Public Defender, Wendell Goad.

“I got arrested here April 20, and then I got out seven days later on pre-trial home detention, and I think about 12 days later, I got arrested in Marshall County for theft at Walmart. I was trying to get money to get drugs,” said Eskridge.

While Sherry and other drug case defendants are taking advantage of their time at home, seeking that last high before their case is closed, Judge Hall estimates they’re costing taxpayers $5,000 to $10,000.

“They’re not going to stop using until they address that problem, and that’s what we need to focus on,” said Judge Kim Hall.

“In a small county, we’re very fortunate to have people in place that are willing to try anything and everything to change what hasn’t been working,” said Starke County Probation Officer, Chuck Phillips.

As of August, they’re experimenting with an expedited docket.

“So we’ve taken the normal docket, which would be somewhere around 100 days to 120 days for the case to kind of get resolved…to be resolved in 30 to 60 days, and the focus then is on a conviction and treatment,” said Judge Hall.

“I think it’s good, because I think just getting sentenced to a bunch of time---it just forces you to get clean while you’re in jail. It doesn’t take care of the problem. If you’re forced to do it, it usually doesn’t stick,” said Eskridge.

“Our hope with the expedited docket is that as people continue to come into the court system with their substance abuse issues, we take the legal system and instead of having it serve as a hurdle that they have to jump over in order to get to the finish line. We want to turn it around and use it as a fast lane to treatment,” said Judge Hall.

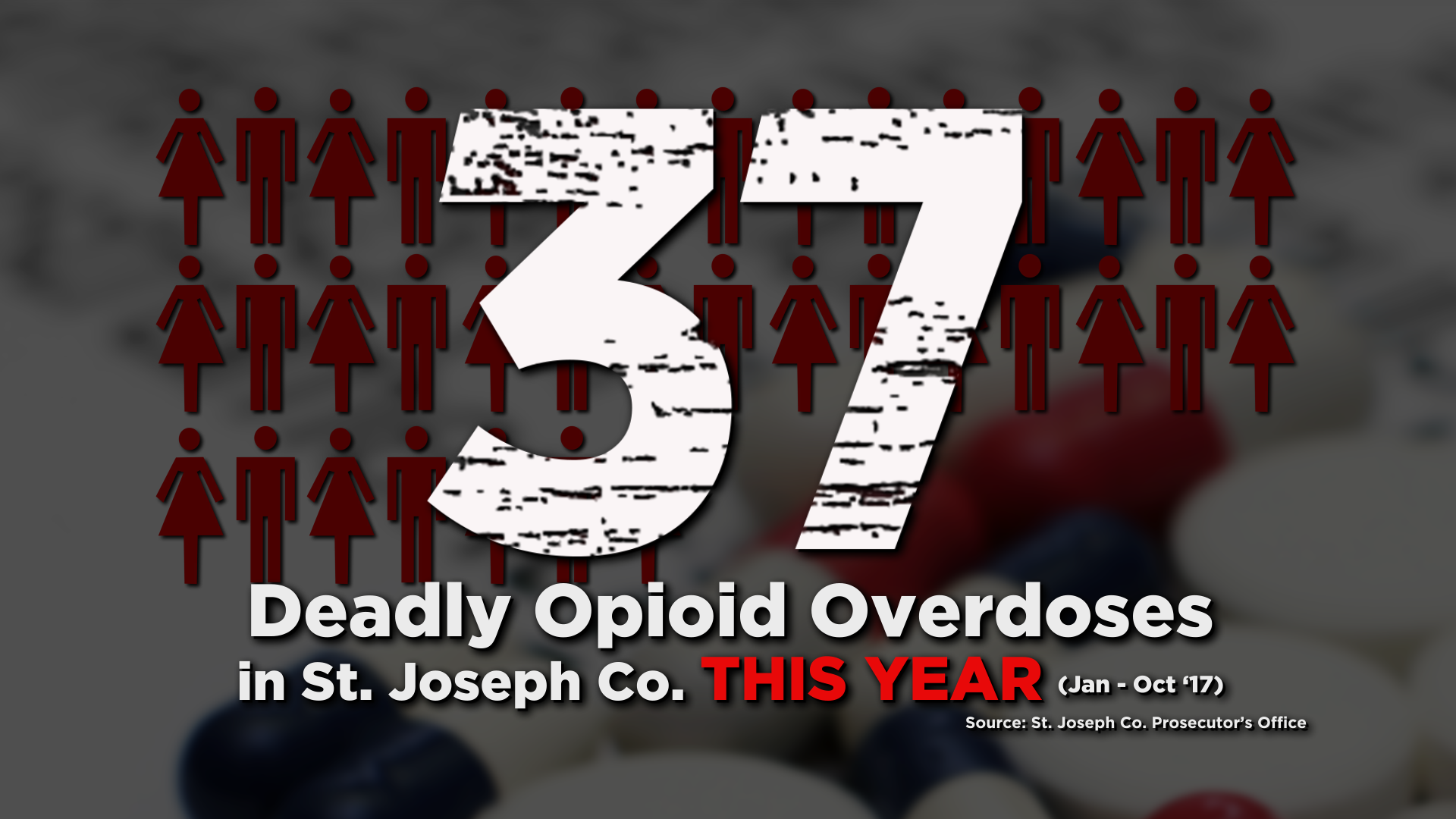

Since the 90’s, St. Joseph County has been sending its drug offenders down the fast track through its drug court.

"The idea at the time was to take low-risk drug offenders and get them into treatment quickly with the carrot that their case would be dismissed and with the hope being that recovery would stick and they wouldn’t be back in the judicial system,” said St. Joseph County Superior Court Judge Jane Miller.

Judge Jane Miller says opioids have forced them to change their M.O. in the last five years.

“It’s been a huge explosion in the number of people coming into our program suffering from an opioid addiction…Now, 55 of the 90 people that are in our drug court identify opiates as their drug of choice,” she said.

“When you’re dealing with heroin addiction, in a very immediate way, you are dealing with a life and death situation in an immediate way that you don’t experience with other forms of addiction,” said Judge Miller. “A heroin addict can fairly easily die with a needle in their arm where there’s no chance to revive them.”

“You want to be done with it, but it’s a very powerful thing. You don’t want to get sick, and you’re scared of the change really,” said Sherry.

Judge Miller says they started considering other options besides forcing addicts to quit cold turkey.

“So now we have I would say half a dozen to a dozen people in our program that are using Saboxone and I would say a couple people that are using Methadone as well,” said Judge Miller.

She said others receive the Vivitrol shot.

All of these routes are at least partially funded by the Recovery Works program enacted by the state in 2015, once government leaders really began to actually see the faces of addiction.

Some are their colleagues.

“I’m a recovering alcoholic, and I’ve been sober for quite a while,” said Judge Miller.

She’s been sober for more than two decades.

“I had some issues myself with the legal system and some beverage,” said public defender Goad.

The Starke County defense attorney is also a recovering alcoholic, who’s been sober for almost nine years.

“It means a lot to me to be able to be part of this, and to be part of this process that permits people to get clean and sober just as people were part of the process that permitted me to get clean and sober, so I take it as an honor,” said Judge Miller.

“Being down their road like I was at that time, you know, I can get their attention, so I have a little passion there,” said Goad.

“You just have to treat everyone as a human being and they’re someone’s brother, someone’s son, and you can’t lose sight of that,” said Judge Hall.

Now that key players in the judicial system are removing their jade-colored glasses, they can begin to answer the critical question: “What is the unique capability of justices to effect an impact on this epidemic.

“I think the unique capability is a lot of these cases end up in our courtrooms…So we have the means to get it done, but let’s make sure we’re doing it right,” said Chief Justice Rush.

The goal is that addicts who come into the system share Sherry’s thoughts when they get out.

“You know, before when I got clean, I still had that thought like I’ll be able to use again, and now I don’t even have that desire, because I’m just sick of all the chaos it’s caused my life. Just time to stop,” said Eskridge.

Sherry is currently going to the health center Porter-Starke Services for intensive outpatient program classes.

When the new judicial national task force meets for the first time on November 13 in Washington D.C., among many other things, they’ll be discussing how to better integrate treatment programs like Sherry’s into the court system.