Waterspout season underway: expect to see significantly more waterspouts on the Great Lakes

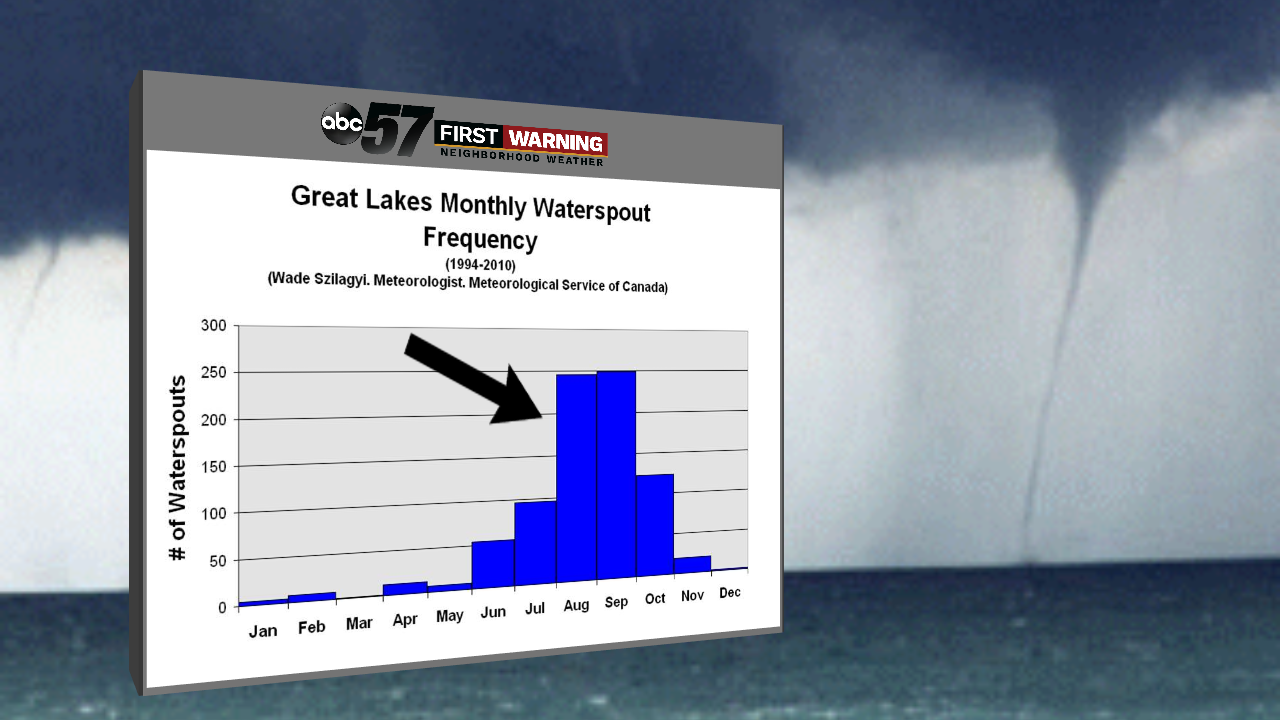

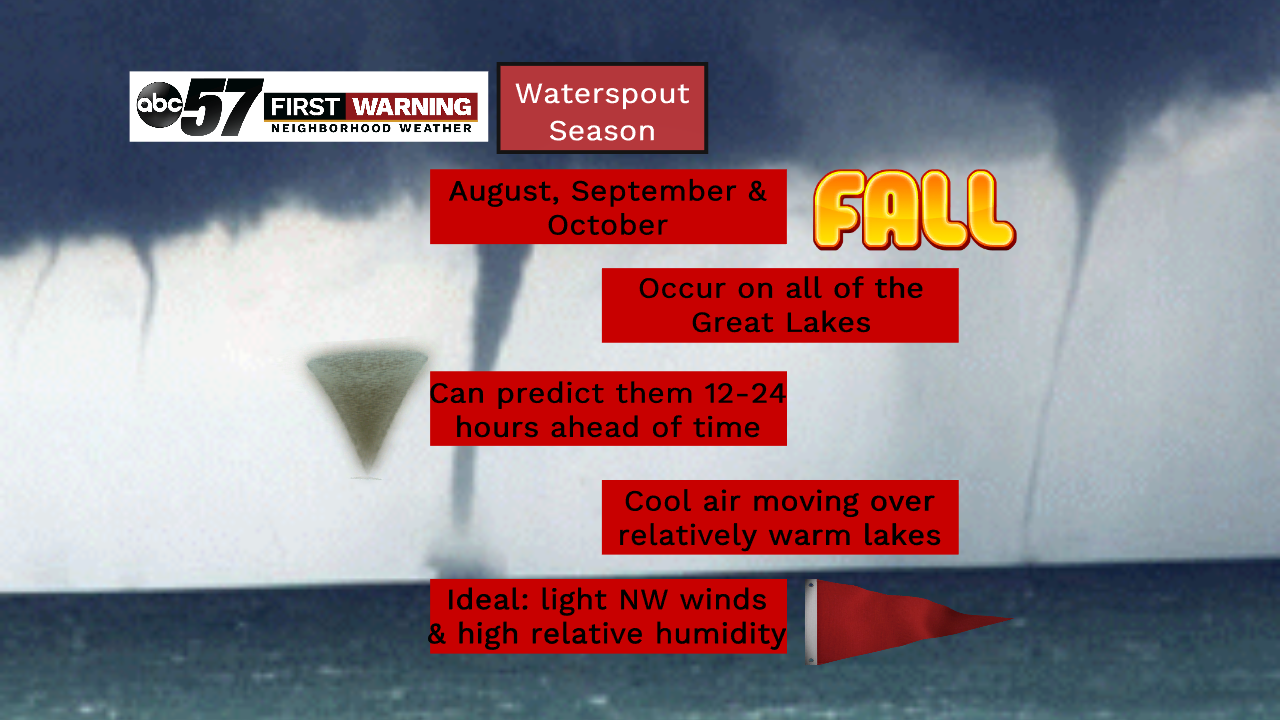

It may sound odd, but yes, there is a such thing as waterspout season on the Great Lakes. It's a period in late summer and early fall that features significantly more waterspouts than any other time of the year.

The increase in waterspout activity during this stretch is rather eye-popping. The stretch being referred to is from late July thru mid-October.It's the time of year when the Great Lakes have the warmest water temperatures, and the frequency of cold fronts bringing cold air to the region rises.

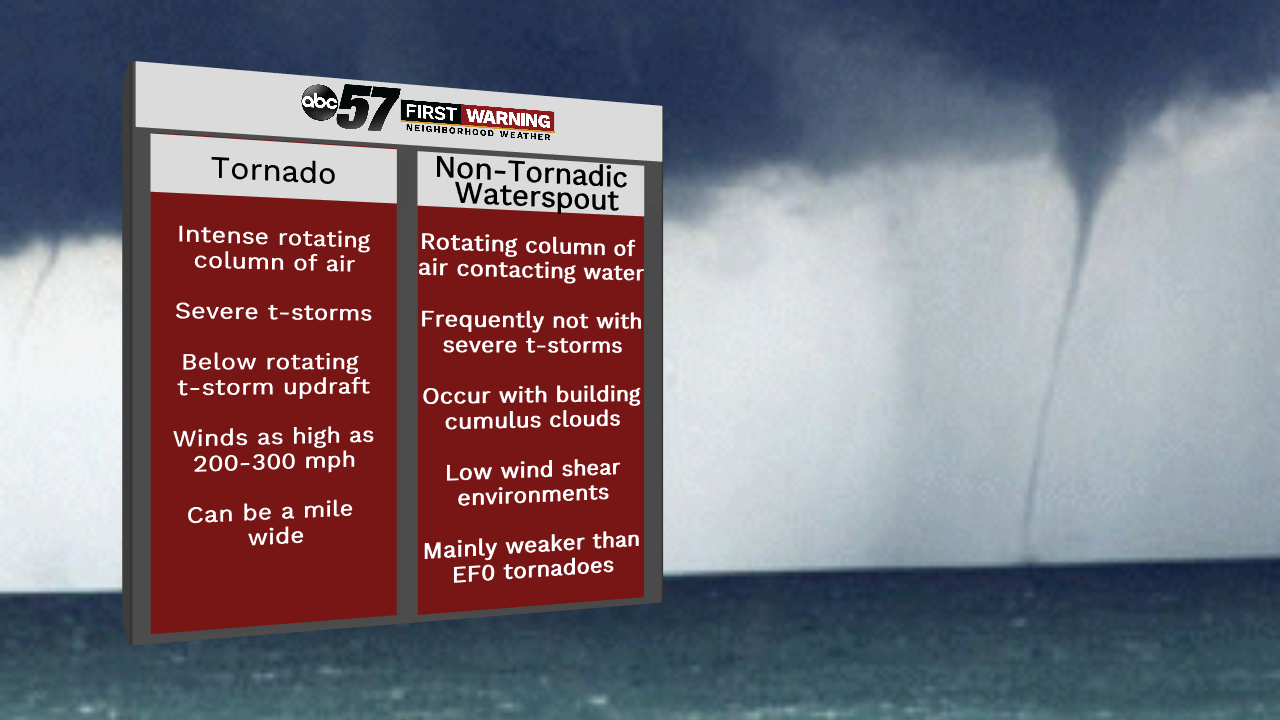

Those are the two components vital in the formation of non-tornadic waterspouts. According to the National Weather Service in Gaylord, Michigan, "Waterspout formation typically occurs when cold air moves across the Great Lakes and results in large temperature differences between the warm water and the overriding cold air."

"They develop at the surface of the water and climb skyward in association with warm water temperatures and high humidity in the lowest several thousand feet of the atmosphere," according to the NWS.

That is the recipe for non-tornadic waterspouts, which are the ones we see most often on the Great Lakes. Believe it or not, they typically form from plain old showers that are non-severe, or from building cumulus clouds without any rain at all. This is unlike tornadic waterspouts, which form just like a tornado would over land. Those are on the rarer side and don't have a specific "season."Another name for non-tornadic waterspouts is "fair weather waterspouts." This is for the simple reason that, as mentioned above, big thunderstorms are not needed for their formation.

These waterspouts rarely move onto land, and when they do, they typically don't cause much in the way of damage.

"They are usually small, relatively brief, and less dangerous. The fair weather variety of waterspout is much more common than the tornadic."

When they do form, they only last a few to several minutes. It's important to take them seriously, though, as they can make for dangerous conditions for boaters and persons on the beach.Dr. Joseph Golden, a waterspout specialist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration laid out five stages of the formation of these waterspouts:

- Dark spot. A prominent circular, light-colored disk appears on the surface of the water, surrounded by a larger dark area of indeterminate shape and with diffused edges.

- Spiral pattern. A pattern of light and dark-colored surface bands spiraling out from the dark spot which develops on the water surface.

- Spray ring. A dense swirling annulus (ring) of sea spray, called a cascade, appears around the dark spot with what appears to be an eye similar to that seen in hurricanes.

- Mature vortex. The waterspout, now visible from water surface to the overhead cloud mass, achieves maximum organization and intensity. Its funnel often appears hollow, with a surrounding shell of turbulent condensate. The spray vortex can rise to a height of several hundred feet or more and often creates a visible wake and an associated wave train as it moves.

- Decay. The funnel and spray vortex begin to dissipate as the inflow of warm air into the vortex weakens.

Unfortunately, predicting these waterspouts is not a solidified science yet. Meteorologists can predict whether or not conditions will be supportive of fair weather waterspouts up to a day beforehand.

They look for relatively warm lake temperatures, cold air moving in behind a front, light winds, and high moisture content in the lower atmosphere.

While they are not issued every day, the International Centre For Waterspout Research does put out a Great Lakes waterspout forecast during the summer and fall months that you can check for yourself at the link here.