Plastic use is one of the biggest issues in the green movement and often we see videos plastic trash along beaches and in the oceans. But there's more to this than meets the eye. Plastic just about everywhere, and most is invisible.

It's called microplastic, and the majority of it is smaller than the diameter of a piece of your hair. The most recent study on microplastic was done on the eastern range of the Colorado Rockies including rural mountains and urban Denver and Boulder. Researchers took water samples at eight locations, filtered out the water and found the presence of microplastic in 90% of the samples.

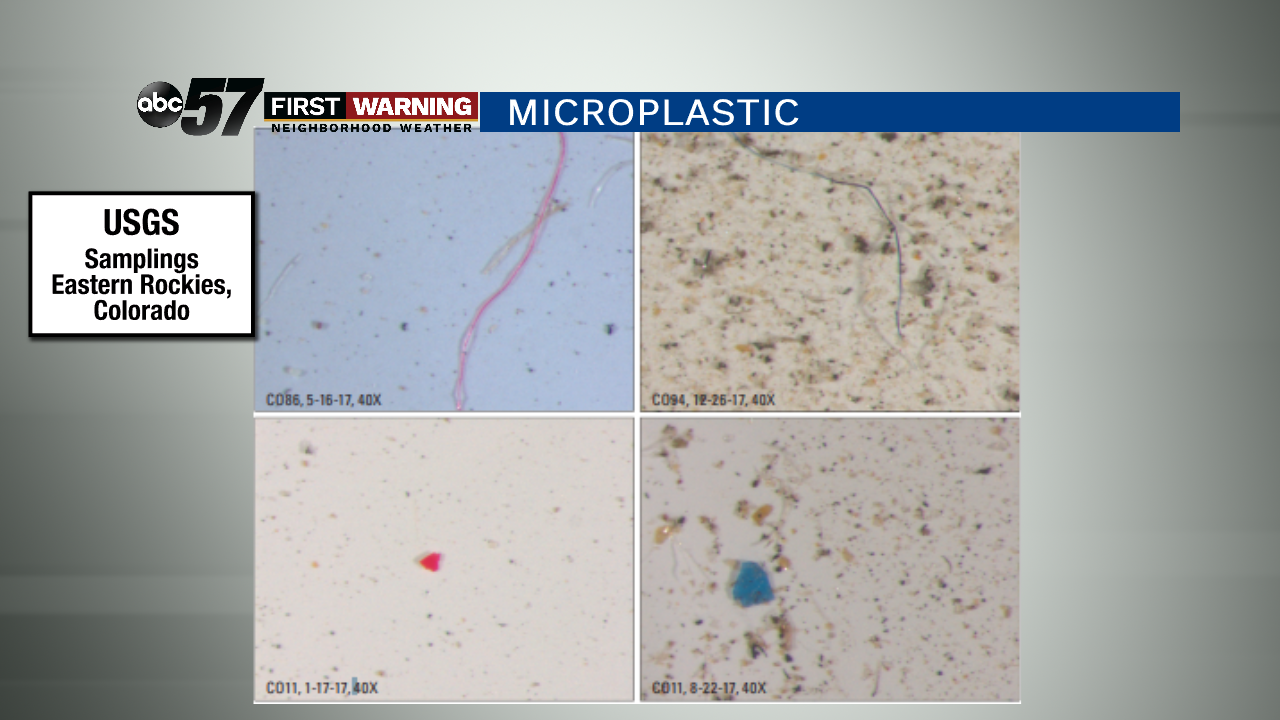

Here you can see what some of those pieces looked like under 40x magnification, meaning they are invisible to the human eye.

Some are fibers and others are pieces. This is not the first study done on microplastic. Research has found microplastic in arctic ice and even in Illinios groundwater sources. Illinois scientists tested groundwater wells and springs throughout the state and found microplastic in sixteen of the seventeen samples.

So how is this happening?

We use a lot of plastic, some of it is recycled and a lot of it goes to waste. Any plastic that goes to waste starts breaking down into smaller pieces. An earlier study done on microplastics in the Pyrenees mountains of Europe found that many of the microplastics were made of polystyrene, polyethylene and polypropylene, which make up most plastic items that we use daily, like one time use water bottles, toys, fasteners and packing materials.

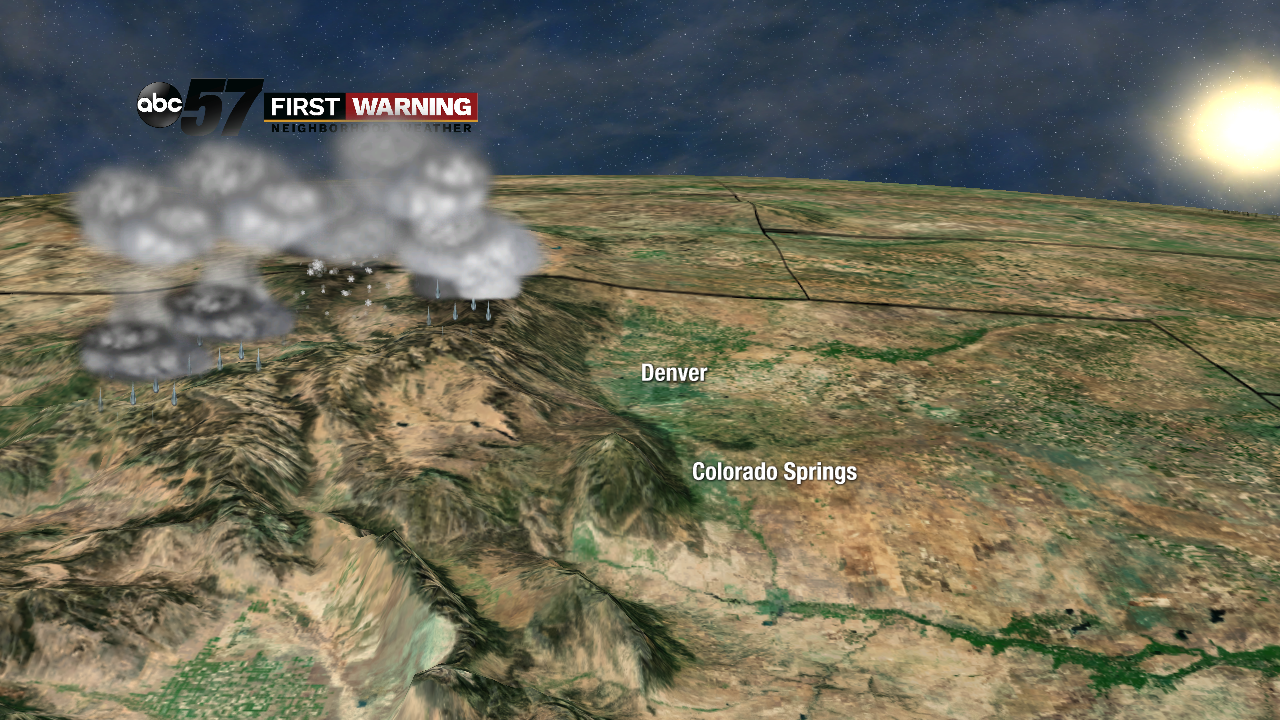

These pieces are so tiny and weightless that they are traveling through our atmospheric systems. Microplastic floats in moving air masses which are pushed around the world by the jet stream. This is just like how dust particles from the Sahara can cause hazy skies in the u.s. research done over a period of five months in the Pyrenees shows that there was an increase in microplastic findings after rainfall, snowfall and windy days. This is how microplastic is ending up all over the place, from the most pristine places on earth like the Pyrenees mountains, to our groundwater.

This subject is so new that scientists do not know what the health or economic impacts will be yet.