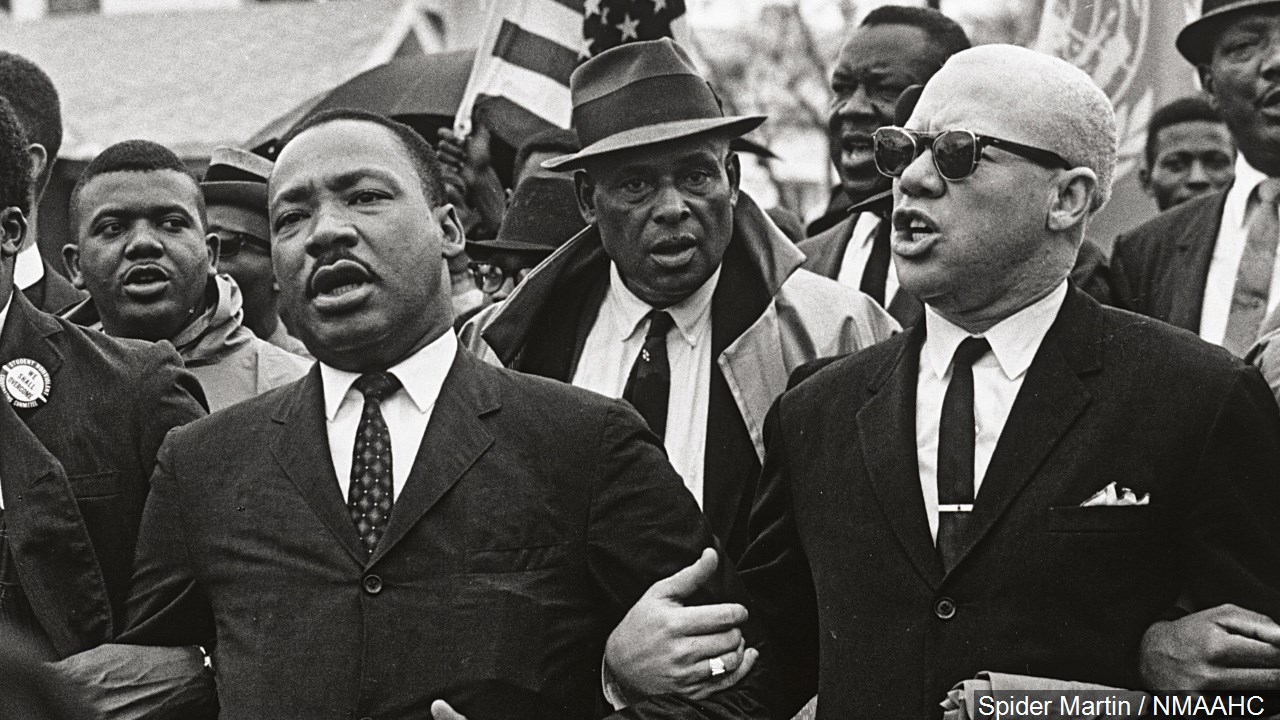

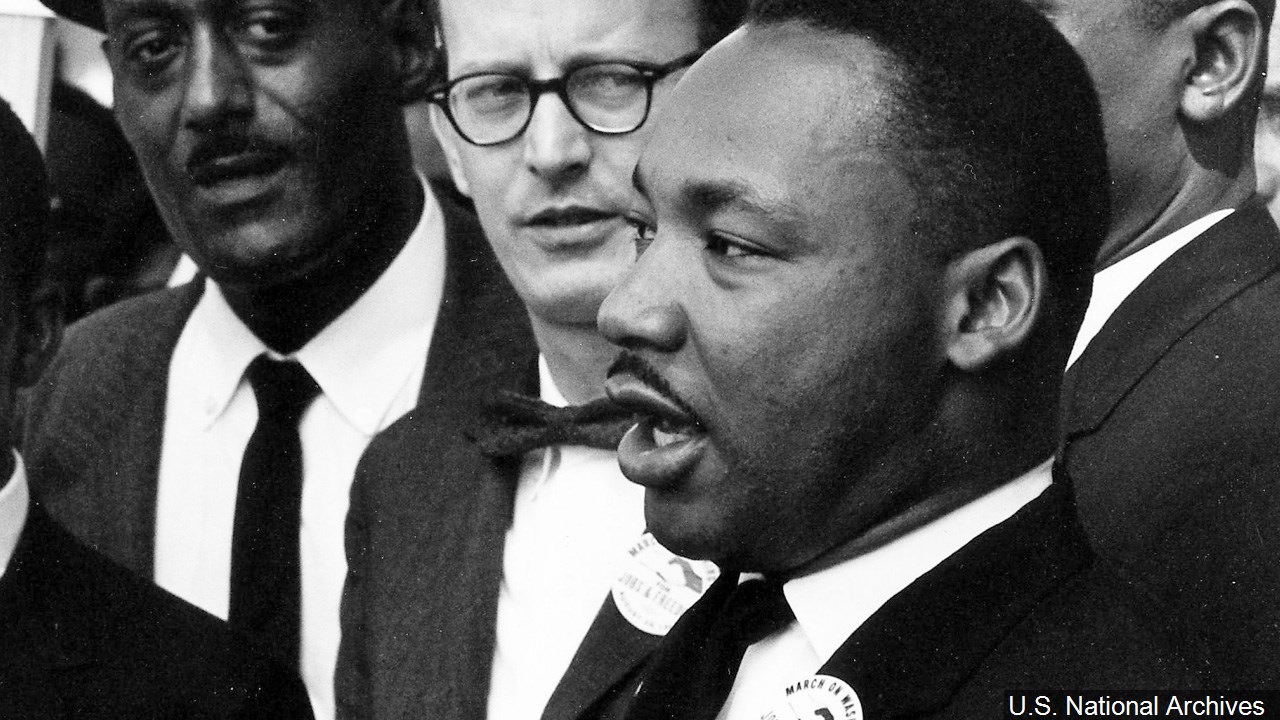

Who is Martin Luther King Jr. to us, 50 years later?

(CNN) -- Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, 50 years ago on April 4, 1968, setting off a period of mourning, reflection and anger that gripped America. He was in Memphis to rally support for striking sanitation work

ers, who were protesting unsafe working conditions, and while on the balcony of his room at the Lorraine Motel (now the site of the National Civil Rights Museum), he was shot once and fatally by James Earl Ray, from the bathroom of a nearby boarding house.By the age of 39, King had become a primary leader of the civil rights movement and had been active since the 1950s as a minister and founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He was an instrumental figure in protests (in Montgomery, Washington, Selma and elsewhere) and in the passage of landmark civil and voting rights legislation. He had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize at 35. In the last years of his life, King faced criticism from some African-American activists who wanted him to employ more confrontational strategies for change. At the same time, he had become more outspoken on issues of poverty and the need to end the war in Vietnam, significantly in the "Riverside Church" speech, delivered in New York a year to the day before his death.

The assassination reverberated powerfully around the world, especially in American cities, where the tragedy sparked unrest in Washington, Chicago, Baltimore, Kansas City, Missouri, and elsewhere. The following week, riots broke out in dozens of cities, in multiple instances warranting the intervention of the National Guard.

King's death (like that of Malcolm X only a few years earlier) radicalized some activists who saw futility in his strategy of nonviolence. At the same time, widespread public mourning for King was key in the passage -- only days after his assassination -- of the Fair Housing Act, the final significant civil rights legislation of the era. President Ronald Reagan signed into law a bill creating a national holiday in King's name in 1983, and King's vision remains the foundational lexicon of the fight for racial equality in the United States.

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of his assassination, CNN Opinion asked a diverse group of activists, academics, public figures and artists: What do you see as the most applicable part of King's legacy? On this occasion, what do you most want to say about him?

The views expressed here are solely those of the authors.

King's place in history is still unfolding

Joseph J. Ellis: The dialogue among Jefferson, Lincoln and King continues

Though it is only a conceit, I like to believe there is an ongoing dialogue on the Mall and Tidal Basin among Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr. Jefferson started the conversation with the magic words of American history: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal." He clearly intended the words to mean that slavery was wrong but never acted on that intention as a statesman or slave owner.

Lincoln did act, in a very big way called the Civil War. But Lincoln failed to take the next step by endorsing a biracial American society.

That was King's mission. He believed that the meaning of Jefferson's magic words had expanded to include blacks as well as whites. Though he delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, he claimed he was collecting on a "promissory note" written by Jefferson.

Whether Lincoln would have felt upstaged by the Jefferson reference can never be known. It is possible that Lincoln heard King's words in the "I Have a Dream" speech as an updated version of his own words in the Gettysburg Address, where Lincoln described "a new birth of freedom," believing that his own words also had an expansive meaning.

Jefferson's response to King's speech is more difficult to imagine. In his own lifetime Jefferson was a truly visionary statesman who could endorse the complete separation of church and state as well as the global triumphs of democracy. But race was his blind spot.

Even though he watched four of his own biracial children by Sally Hemings grow up at Monticello, Jefferson went to his grave believing that blacks and whites could never live together in harmony in the United States. And if and when they did, the result would be the pollution of the Anglo-Saxon race, in his view.

In that sense, King's dream was Jefferson's nightmare. The white racist who shot King on the balcony in Memphis could claim to be acting in Jefferson's name with as much plausibility as King himself.

On the other hand, Jefferson was a firm believer in what he called "generational sovereignty." Though there surely were external truths, each generation needed to rediscover those truths for itself and not be held hostage to the past. History moved forward along a gradually ascending path that Jefferson described as "the progress of the human mind."

King had his own way of describing the same idea. He borrowed the words from Theodore Parker, a 19th-century theologian and anti-slavery advocate: "The arc of the moral universe bends upward toward justice." With these words in mind, I can easily imagine Jefferson smiling from his perch on the Tidal Basin when the Martin Luther King Memorial went up, welcoming him as the third and final member of America's trinity.

In this uplifting version of American history, all three icons nodded their approval when the Museum of African American History and Culture was dedicated in 2016.

Anyone who toured the new museum, however, would be forced to confront the self-evident truth that Jefferson chose to omit from the Declaration of Independence, though he was candid enough to acknowledge it in his correspondence. Lincoln and King knew it too, and both of them were killed by men who felt it in their very bones.

Namely, American society rests atop a deep pool of racial prejudice that has defined the relationship between blacks and whites for most of American history. It is still there and always will be. The conviction that we can and should become a truly biracial society is a recent, mid-20th-century idea.

King was the chief apostle for that idea, which is the reason we honor him with a place on the Mall. But he knew that he would not live to see the Promised Land.

He also knew, as Jefferson and Lincoln knew, that the upward arc of the moral universe was constantly being pulled back to earth by the gravitational force of racism. Every step forward produces progress that generates a backlash.

We currently occupy one of those backlash moments. As I listen to Jefferson, Lincoln and King discussing Trumpworld, that is what I hear them talking about, in worrisome tones.

Joseph J. Ellis is an American historian who won the Pulitzer Prize for "Founding Brothers." He is the author of the forthcoming "American Dialogue: The Founding Fathers and Us."

Sherrilyn Ifill: King's work remains unfinished, but the democracy-building work continues

A decade before his shocking assassination, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., on behalf of the Montgomery Improvement Association, sent a thoughtful letter and a $1,000 check to Thurgood Marshall, then director-counsel and founder of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF), the civil-rights organization I'm now blessed to lead.

King wrote that the purpose of the letter and the modest contribution — which he wished wasn't so modest, perhaps because he knew the real costs of legal representation in the trenches — was to express his "deep sense of gratitude" for our work "for not only the Negro in particular but American Democracy in general."

"You continue winning the legal victories for us and we will work passionately and unrelentingly to implement these victories on the local level through non-violent means," King wrote, singling out our legal assistance in his organization's struggle to help desegregate the Montgomery bus system.

This was no ordinary civic-legal partnership. If Brown v. Board Education spelled the doom of "separate but equal," the lesser known Browder v. Gayle, which we helped litigate in Alabama just two years later, was the doctrine's coup de grâce — a unanimous Supreme Court declined to disturb a lower-court ruling invalidating a series of Jim Crow-era statutes and ordinances that provided for racially segregated buses.

What's most touching to me about King's letter to the LDF is that it came in response to legal victories that were, as he put it, victories for "American Democracy." The rulings were a recognition, at long last, that the Fourteenth Amendment meant what it said when it was ratified in 1868. That the Constitution's promise of equality — the command that no state could "deny to any person ... the equal protection of the laws" — was meant for all of us, regardless of skin color. That exclusion of anyone on account of race could not be tolerated.

And yet, we're still fighting to make our Constitution's true meaning real. We're still fighting to make sure no one's vote is suppressed. We're still suing to ensure that the Fair Housing Act, a law enacted in the very wake of King's death, is enforced to its fullest extent. We're still fighting school districts that believe a segregated education is in children's best interests. We're still fighting so that police departments that brutalize communities of color are held to basic principles of constitutional policing. We're still fighting so that immigrants aren't targeted for expulsion from this country.

Worse yet, when it is the president of the United States himself who is pushing an unconstitutional vision of America — by casting this struggle for basic dignity and equality as a political tool to denigrate black and brown people, all the while stoking white resentment and victimizing himself — it is clear that we're far from living up to King's ideals.

Today, 50 years since his death in Memphis, we're in a moment. A moment when I truly believe we are being driven to confront that rot at the foundation of our democracy. A rot we have papered over for too long. It is weakening every pillar of our democracy — up to and including the highest office in our land.

Just a month before King's death in 1968, Jack Greenberg, our second director-counsel after Marshall, met with Dr. King to discuss our next partnership: our representation of participants in the Poor People's Campaign to advocate for fair wages, better jobs, employment training and more — the next logical step in King's vision of true equality. That he was killed while leading such an effort among striking sanitation workers in Memphis is a tragic testament to what was destined to be the next phase of his legacy.

But to this day, I'm heartened as I look back on that civic-legal bond we shared, and his insight that our connection was "the most powerful and constructive avenue" to bring African Americans to their full measure as citizens. That much is still true today, or else we would've given up the fight a long time ago.

King's work remains unfinished, but the democracy-building work continues — with lawyers and activists working hand in hand to reach the promised land that King saw but couldn't yet enter.

Sherrilyn Ifill is the president & director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund Inc.

To read the full story about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr's mission and stamp on American civil rights, click here.