Meteotsunamis: a forgotten, dangerous and possibly deadly hazard

Did you know tsunamis can occur on the Great Lakes, including Lake Michigan? Not only do they occur, but they happen more often than you probably think.

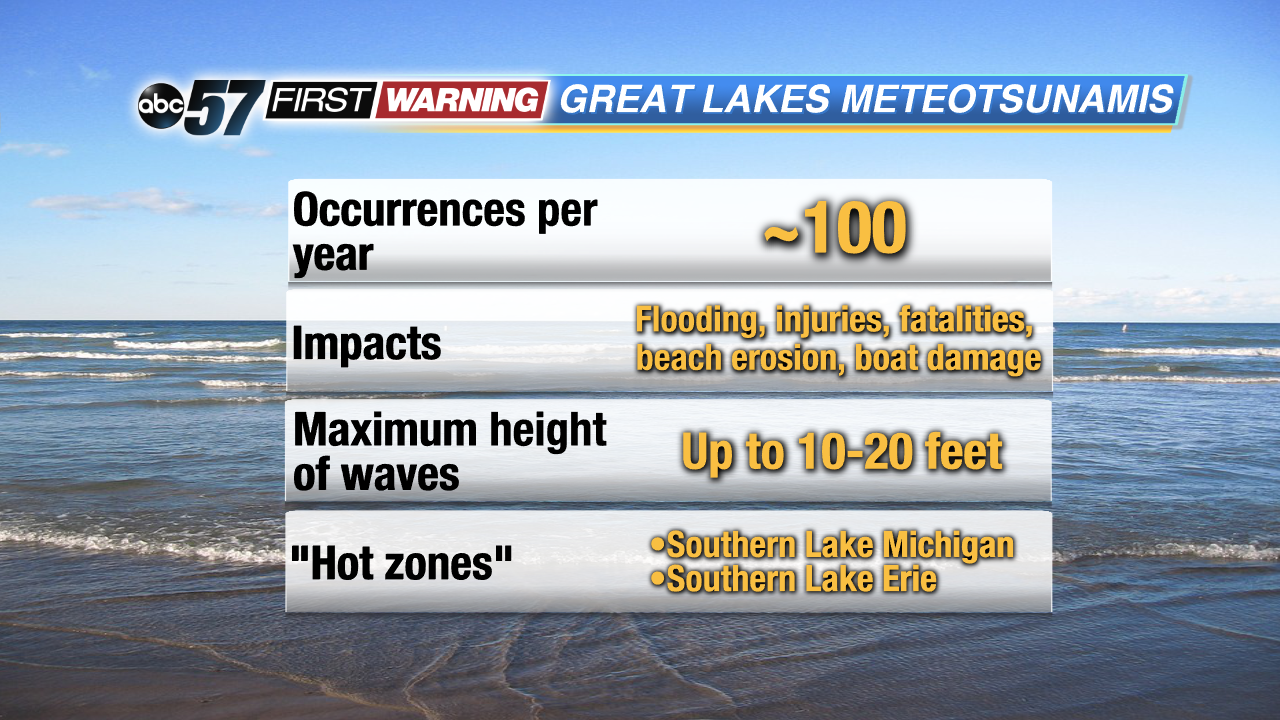

They are called meteotsunamis, and they can pack quite a punch. Between the five Great Lakes, we see roughly 100 meteotsunamis each year. Most of them aren't even noticeable. Some, on the other hand, are impactful and present a danger to the shoreline and people.Eric Anderson, a physical oceanographer who specializes in meteotsunamis with NOAA's Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, tells ABC 57 News that meteotsunamis "cause a number of things; fatalities to swimmers that have been in the lake. People that have been on the pier, or on a break wall have been washed into the water. Flooding events [and] damage due to flooding. [They push] debris from the lake up onto shore, sometimes into cottages or houses on the shoreline, [thus] swamping marinas and even capsizing boats."

Something else to keep in mind is that there are two distinct types of dangerous waves on the Great Lakes (see video above). There are meteotsunamis and seiches. According to NOAA, they are often grouped together in the same category. However, they differ in a few ways. Seiches are standing waves generated by winds crossing over a lake. They have a period of at least three hours. Think of a bathtub when the water at one end is high and the water level at the other end goes down. These occur slowly and can cause flooding on the side of the lake where the water rises.

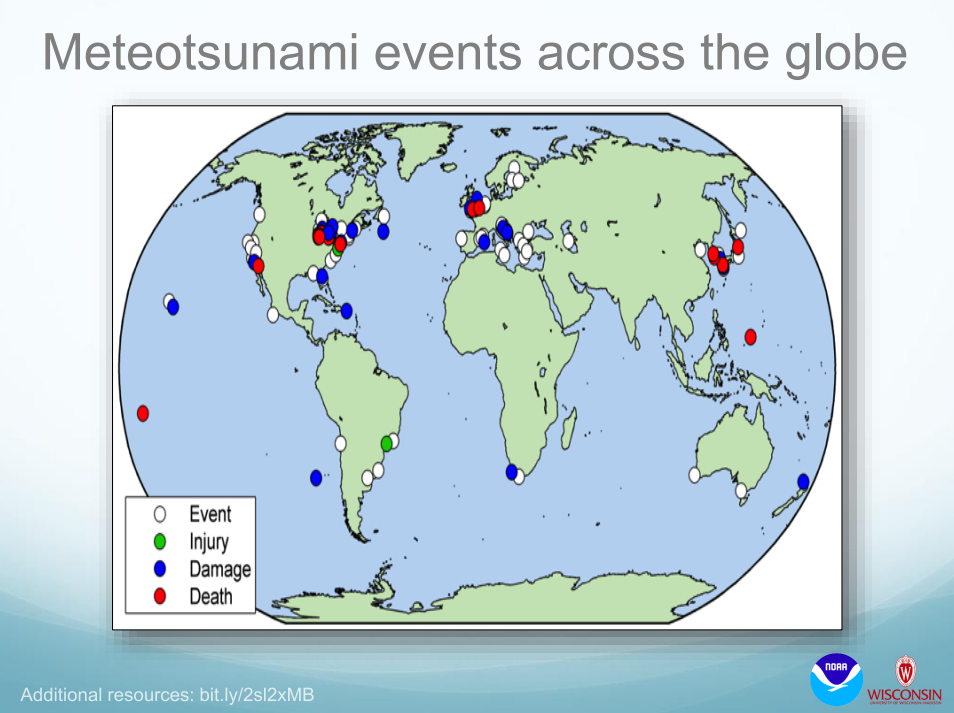

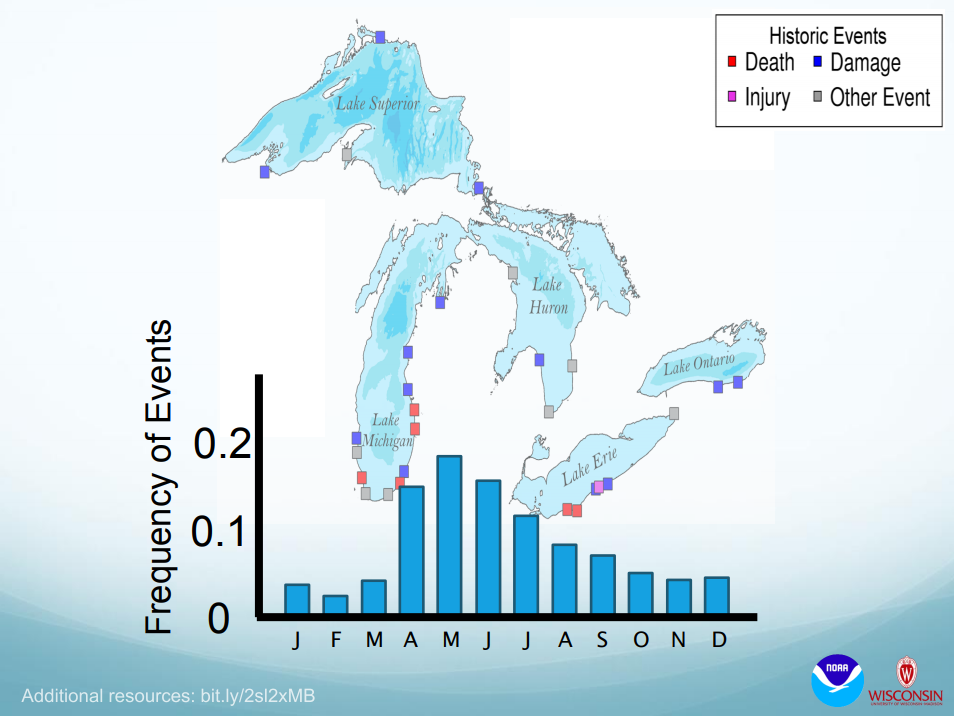

Atmospheric pressure plays the biggest role when it comes to meteotsunami formation. As storms cross Lake Michigan, their lower pressure and strong winds can generate a wave or waves. Meteotsunami waves hit faster than seiches, and the period between waves can be as short as two minutes. They can both be dangerous in their own respective ways. Let's focus on meteotsunamis. They occur across the globe, including the Great Lakes. In fact, the Great Lakes region has seen more meteotsunamis responsible for deaths, injuries or damage than any other part of the world! And, believe it or not, part of Lake Michigan is deemed a "hotspot" for them."Southern Lake Michigan and Southern Lake Erie seem to be the hotspots for meteotsunami activity," Anderson says. He went on to say that "most meteotsunamis, historically, have happened in the late spring and early summer...peaking in May, starting in April and ending in late June, maybe early July."

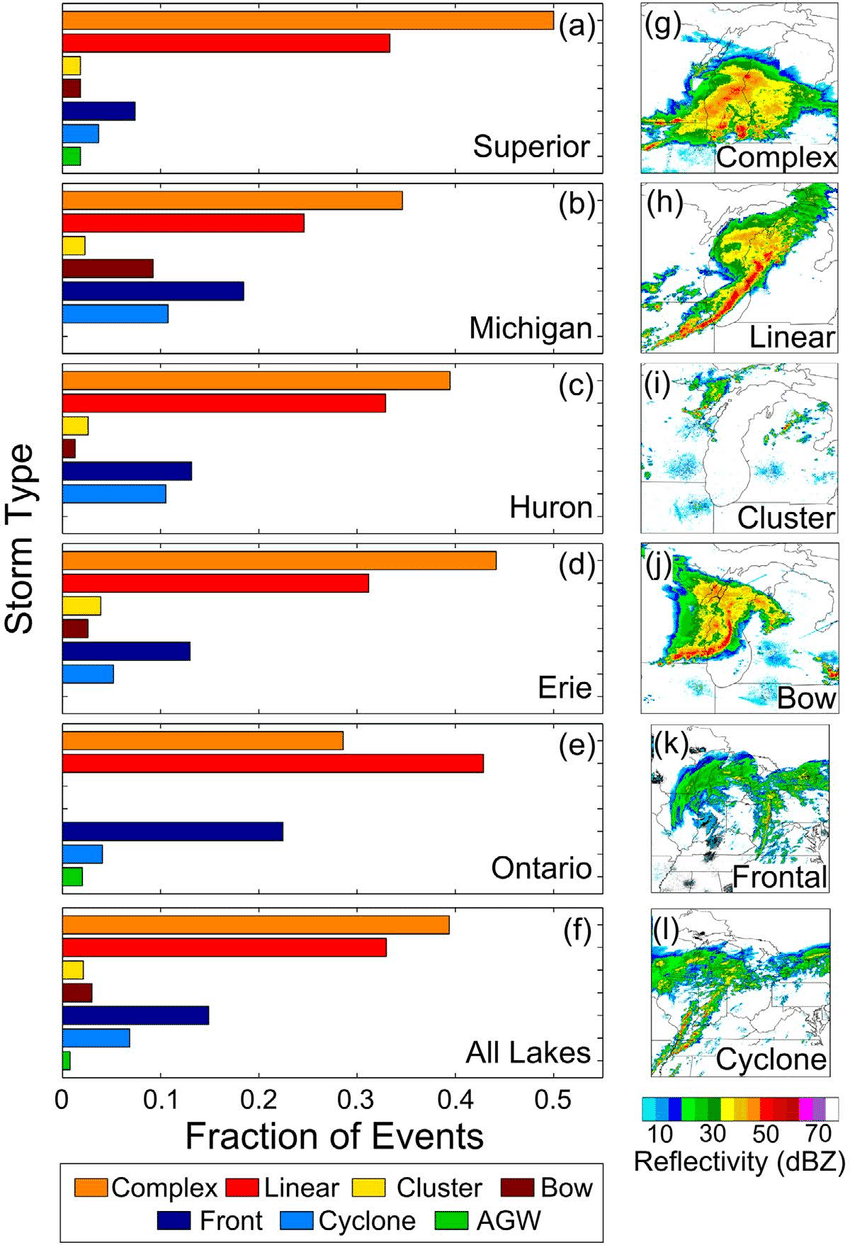

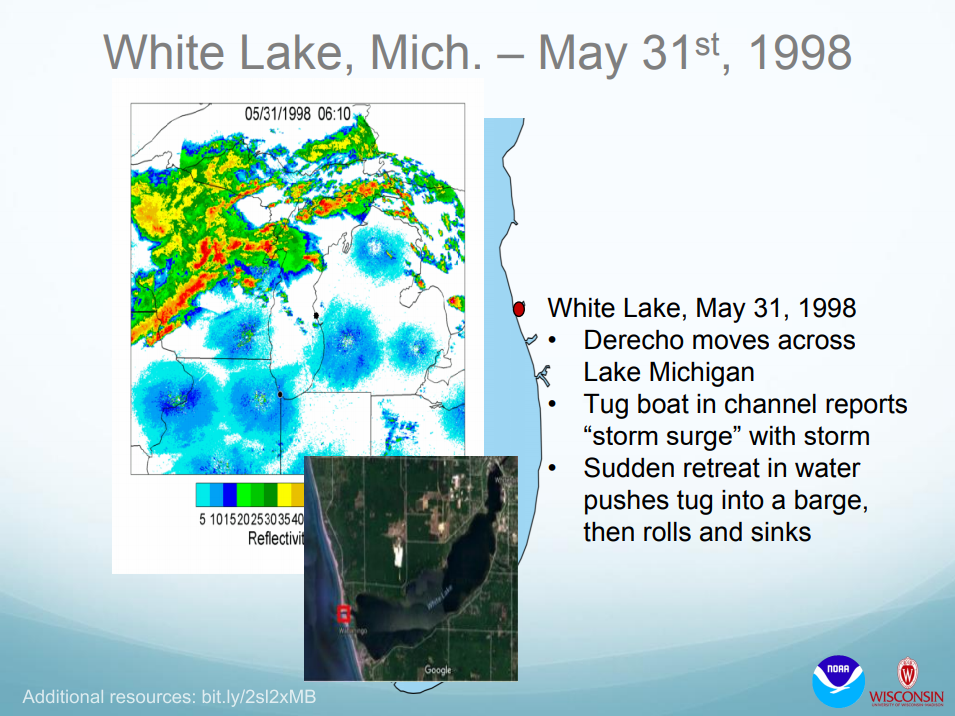

The reasoning behind meteotsunamis peaking in the April to July period is simple: that's when we see the most convective activity in the Great Lakes region. In other words, it's the period when we see the most thunderstorms and even severe thunderstorms. Lake Michigan specifically sees meteotsunamis develop due to all types of thunderstorms and even systems:•Storms: complexes, lines of storms, clusters of storms, bow echoes

•Systems: strong cold fronts, strong low pressure cyclones

As mentioned earlier, not every meteotsunami is large. Some are barely even picked up by buoys in the lakes. Occasionally, though, we get ones that can prove to be very dangerous with heights upwards of 10 feet, if not larger."That's certainly enough to be dangerous," Anderson says. "I'll also mention that even a relatively short wave, maybe one that's only a foot tall, [can be dangerous]. Imagine that these meteotsunamis are about a kilometer long. A foot of water [tall] by a kilometer [long] is a lot of water to move in and out over, say, 20 minutes. And that's when it can be really dangerous."

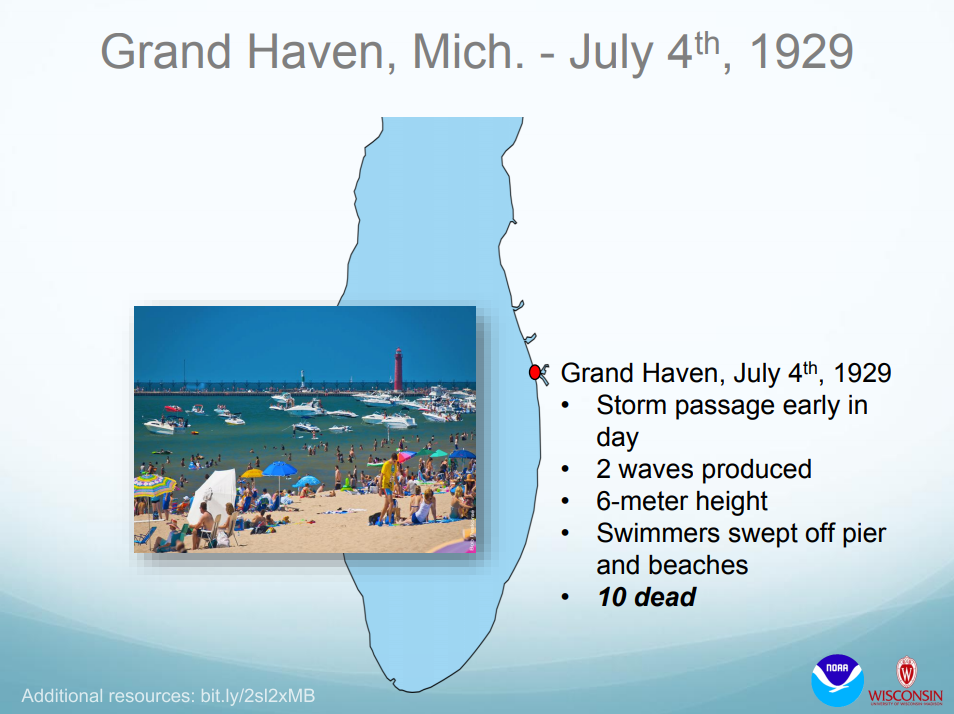

Several incidents have been documented in the Great Lakes of meteotsunamis that have caused extensive damage, injured someone or killed someone. One example is the Grand Haven meteotsunami of 1929. A storm passed early in the day, producing two waves after the storm passed. The waves were nearly 20 feet tall, and swept swimmers off the pier and beaches seemingly out of nowhere. In the end, 10 people lost their lives.

In 1954, a 10-foot wave hit Chicago and wound up killing seven fishermen. Closer to home, seven people drowned due to what is referred to as a moderate meteotsunami that struck Sawyer, Michigan, in 2003. These types of events don't happen every year, but they can occur at any given moment if the meteorological conditions are just right. When asked about any sort of preparation for meteotsunamis, Anderson says there's not much you can do aside from being cognizant of your surroundings on a windy or stormy day. Even after a storm passes, it's important to be careful because the wave(s) generated by the storm could lag well behind the storm itself. Despite all of this, he went on to say that meteotsunamis are not a reason to avoid visiting or living along the Great Lakes.And, while they may be difficult to accurately predict at this juncture, Anderson says that in the next few years, NOAA should have the ability to issue something along the lines of a "meteotsunami watch" if conditions seem supportive of meteotsunami development. He says it would be similar to tornado watches in the sense that they would be issued hours or even a day ahead of time depending on the situation.